Jason Papin is a biomedical engineering professor and serves on the pan-University Global Infectious Diseases Institute. (Photos by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Editor’s Note: One in an occasional series about University of Virginia faculty members who are helping to make the University both great and good. Today’s installment features Jason Papin, a biomedical engineer who uses lab work and computer algorithms to study antibiotic-resistant bacteria, infectious diseases and more.

In October, University of Virginia biomedical engineering professor Jason Papin published an op-ed in The Hill about the alarming growth of antibiotic resistant “superbugs.” More than 700,000 people die annually from incurable drug-resistant infections, he noted, and that could jump to 10 million in as few as 30 years.

How do we stop that and other global health crises? Papin, who has been at UVA since 2005, argues the solution has just as much to do with data science as it does with lab work – specifically the development of computer models that can predict cells’ changes and reactions.

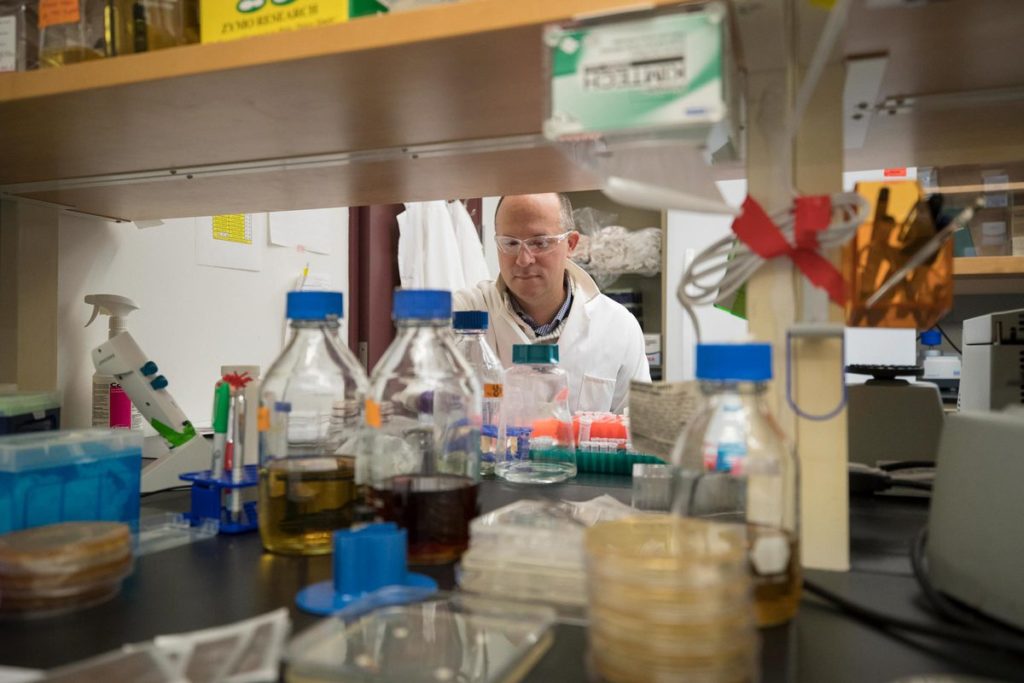

In his lab at UVA, Papin and his team – a research faculty member, postdoctoral fellow, four Ph.D. students and three undergraduates – are using both laboratory science and computer algorithms to predict how our cells behave.

The process starts in the lab, where researchers grow bacteria with slight variations and track how the cells respond in different environments. Which genes are activated in certain environments? Which are not? Why?

Papin and his team use both laboratory experiments and computer models to predict how cells will change and react in various conditions. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

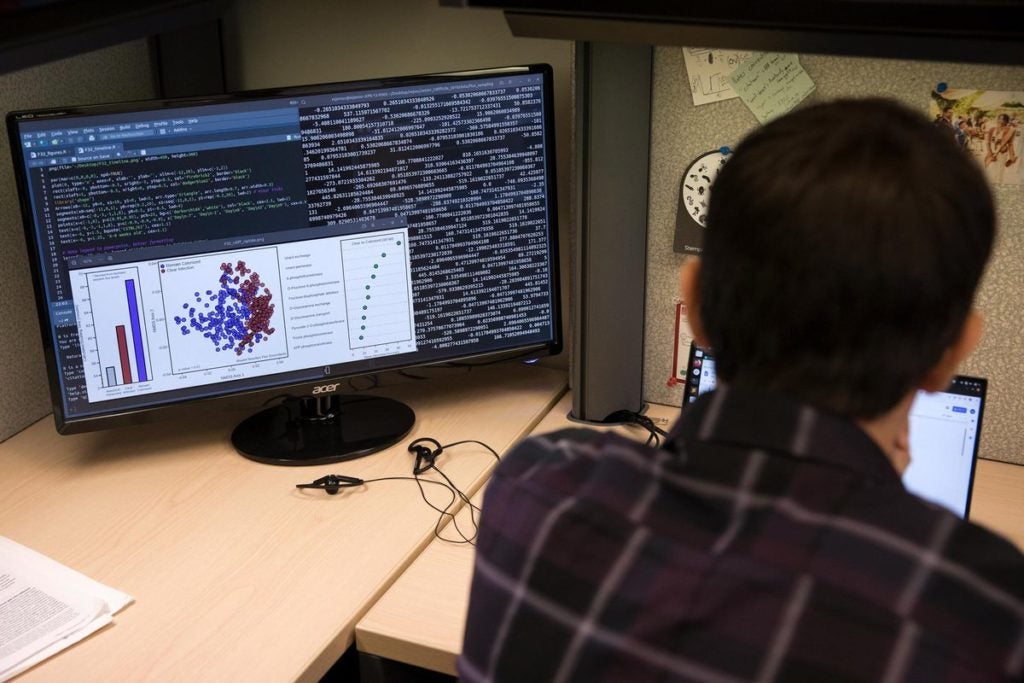

To find out, researchers develop computer simulations and algorithms, plugging in information from the lab. The more information the algorithm receives, the more predictive it becomes.

“We then sort through those predictions, check them against published literature and, if there are gaps or phenomena we don’t understand, return to the lab to do an experiment to understand why the prediction was correct or incorrect,” Papin said.

With that method, the possibilities are nearly endless. Researchers can, for example, identify cells best equipped to respond to a particular drug, or track how bacteria evolve and adapt during the course of an infection. They can also work to predict how antibiotic resistance develops or changes, or how different organisms in our microbiome interact with each other.

Computer models can generate millions of data points, providing insight on everything from how bacteria evolve to how cells will respond to a particular drug. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

“We can generate thousands and millions of different data points and see how all of those pieces connect to each other,” Papin said.

Recently, for example, students in Papin’s lab studied different ways bacteria respond to existing antibiotics. They found that bacteria that are resistant to one antibiotic can lose that resistance when treated with another antibiotic. In addition, they discovered that antibiotic-resistant bacteria have altered ways of interacting with the environment.

“The solution doesn’t necessarily have to be developing new antibiotics,” Papin said. “It might mean using the ones we have more intelligently or differently.”

Such data is crucial to human health in many ways, Papin said, because there are at least as many microbes in and on our bodies as there are human cells, if not more.

“We have to understand how all of these cells interact with each other and with human cells, and how they communicate with each other,” Papin said. “Those complex relationships are key to so many treatments.”

UVA is an exciting place to do that work. The schools of Medicine and Engineering are located together, promoting all sorts of collaboration, and the newly launched School of Data Science is building on growing momentum in the field across Grounds.

The Schools of Medicine and Engineering seen from above. Their close proximity makes collaboration easy. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak, University Communications)

Papin already has a close relationship with School of Data Science Dean Phillip E. Bourne, who is also a professor of biomedical engineering. Bourne was one of Papin’s professors when he was in graduate school at the University of California-San Diego.

“There is a growing number of connections between data science and other disciplines across the University,” said Papin, who also serves as an associate director of the pan-University Global Infectious Diseases Institute. “It’s exciting.”

Papin’s interest in bioengineering dates back to high school.

“I knew I liked math and biology, but I did not necessarily want to be a physician,” he said. “As an undergraduate, I started learning about computer models of biological systems, and just how much biological data we could generate with new experimental technologies. I was immediately interested in the idea of using computer models to predict how cells behave and figure out things like new drug targets.”

His focus narrowed to microbes and infectious diseases after he spent two years doing mission work in Brazil, where he saw firsthand the toll infection could take.

“You see the impact of these clinical problems,” he said. “It just all came together for me.”

Now, Papin is committed to equipping the next generation of biomedical engineers to harness the power of data science.

Papin emphasizes data science in every class he teaches, whether he is working with undergraduate, master’s or Ph.D. students. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

In his op-ed, he argued that university biomedical engineering departments must give students consistent opportunities to solve problems with data and understand the best analytical tools to address each unique challenge. At UVA, where data science is one of the biggest strengths for the Department of Biomedical Engineering, he acts on that principle in every class he teaches, whether classes for master’s or Ph.D. students or lectures and seminars for undergraduate students.

Some of his most rewarding moments come when former students go on to publish work of their own. Right before we spoke with him, Papin received an email about a former Ph.D. student, now a professor at the University of Illinois, who had just published new research.

“That was pretty cool to see,” he said, smiling. “I have had some marvelous students come through my lab who have gone on to do many exciting things, and that is very rewarding.”

Day in and day out, Papin works with students in his lab. Many of them have gone on to lead similar labs around the country. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Filed Under: Education, Featured, Media Highlights, Research