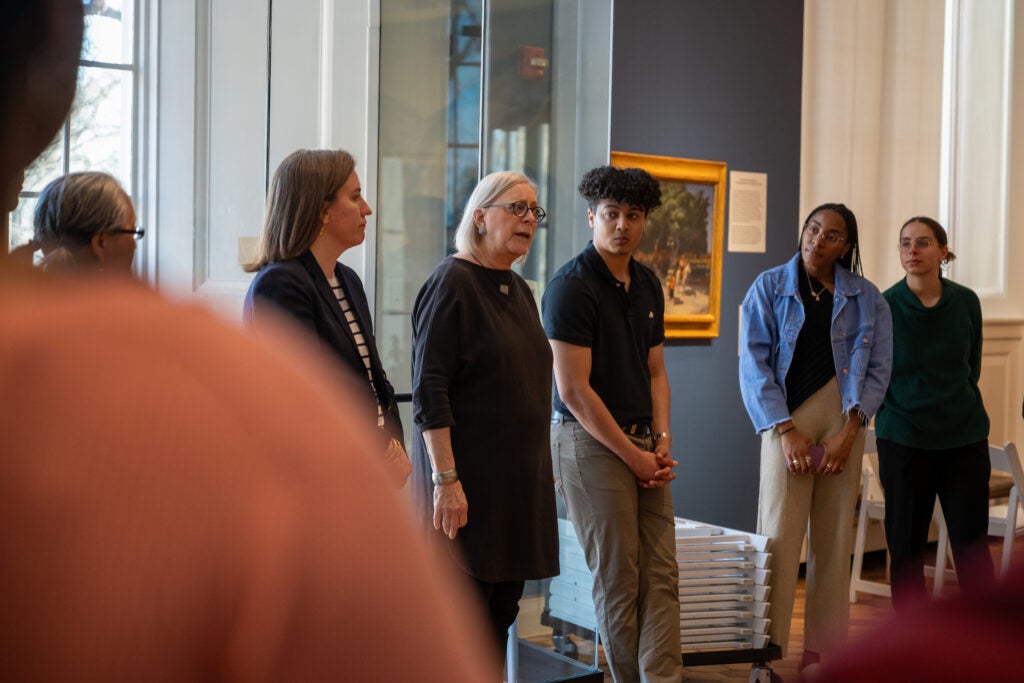

During the Clinician’s Eye workshop, School of Medicine faculty and museum leaders speak with first-year medical students at The Fralin Museum of Art at UVA.

More than 100 U.S. medical schools today partner with art museums to offer guided engagement with visual art to improve apprentice physicians’ observation, communication, teamwork, and other core clinical skills. The University of Virginia School of Medicine is one of the early pioneers of this effort, having offered art-based clinical skills training for medical students through the Clinician’s Eye workshop since 2013.

Clinician’s Eye is a dynamic partnership between The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia and the School of Medicine’s Center for Health Humanities and Ethics. The program, co-led by workshop creator M. Jordan Love, Fralin’s Carol R. Angle Academic Curator, and emerita professor of medical education in health humanities Marcia Day Childress, PhD, and museum docent, began 12 years ago as a non-credit medical school activity. For the last five years, the two-hour workshop has been a required element of Foundations of Clinical Medicine (FCM), an 18-month preclinical doctoring skills course. In a single week, on four successive afternoons, all 160 first-year medical students and their FCM physician coaches complete the museum workshop. This year, the Clinician’s Eye workshop occurred in the last week of March.

A short walk from the School of Medicine, The Fralin is a convenient learning lab. As a neutral space apart from hospital routines and hierarchies, the museum helps learners slow down, sharpen their looking and listening; retreat from decision algorithms; tangle with ambiguity and uncertainty; and wonder. Art methods and materials illuminate human experiences of illness and mortality and let trainees practice skills like reflection and tolerance of uncertainty that can be challenging to acquire via medical didactics.

A short walk from the School of Medicine, The Fralin is a convenient learning lab. As a neutral space apart from hospital routines and hierarchies, the museum helps learners slow down, sharpen their looking and listening; retreat from decision algorithms; tangle with ambiguity and uncertainty; and wonder. Art methods and materials illuminate human experiences of illness and mortality and let trainees practice skills like reflection and tolerance of uncertainty that can be challenging to acquire via medical didactics.

“Working with art in the museum’s safe space prompts clinicians’ own storytelling. Participants speak and listen to each other about experiences that have moved them, or that may have seemed unspeakable. Some students even recall and reaffirm the values that brought them into medicine,” stated Professor Love.

Connecting Art to Clinical Care

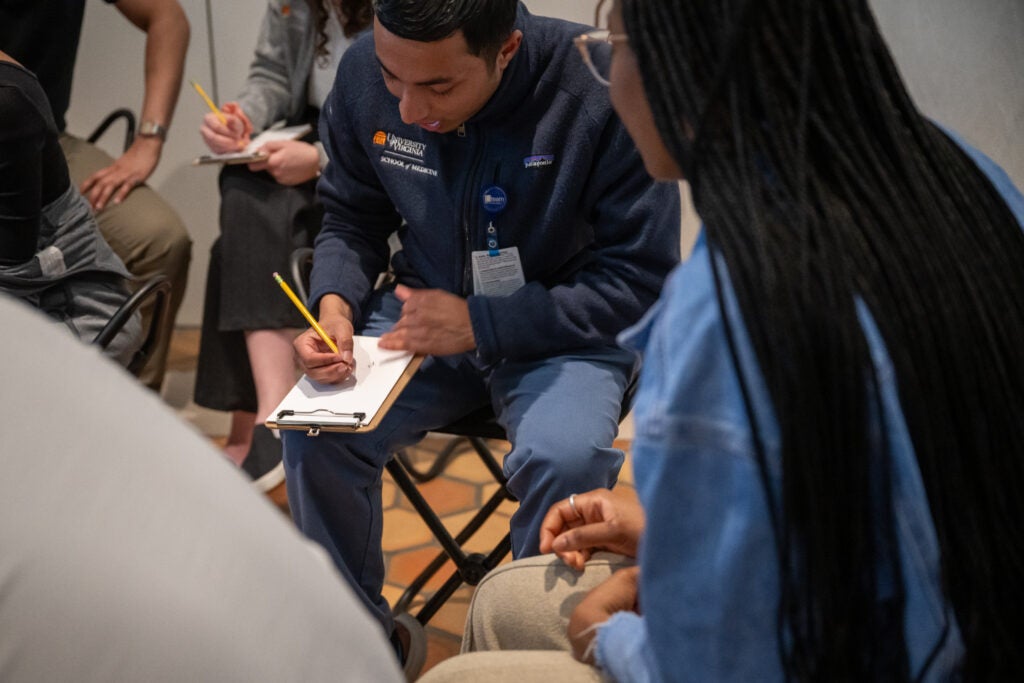

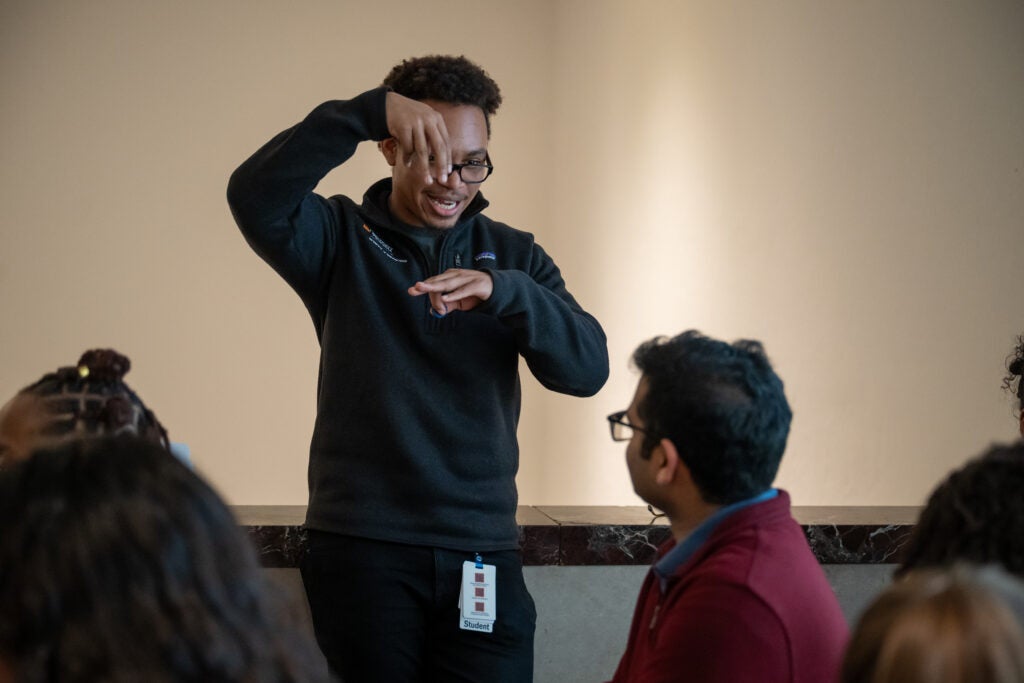

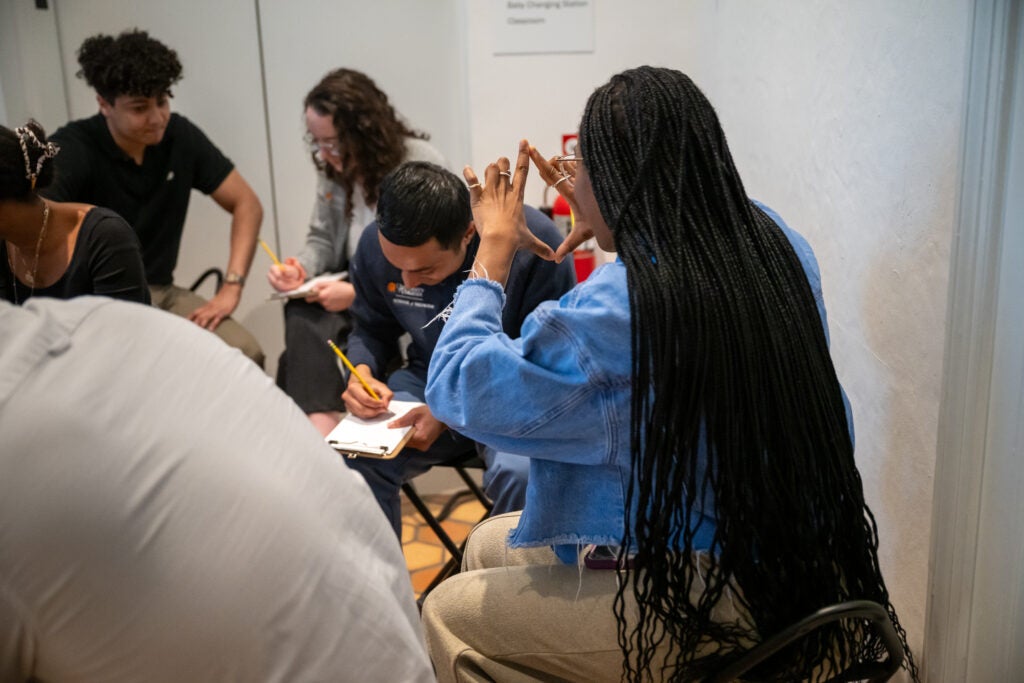

When students arrive at The Fralin, they’re met by museum educators with healthcare expertise who guide them in observing and responding to art. Through interactive exercises, they employ skills of visual attention and active listening, teamwork, cultural and emotional openness, reflection, and tolerance for uncertainty. This practice in turn can improve student doctors’ diagnostic acumen, communication, collaborative thinking, emotional resilience, and wellbeing.

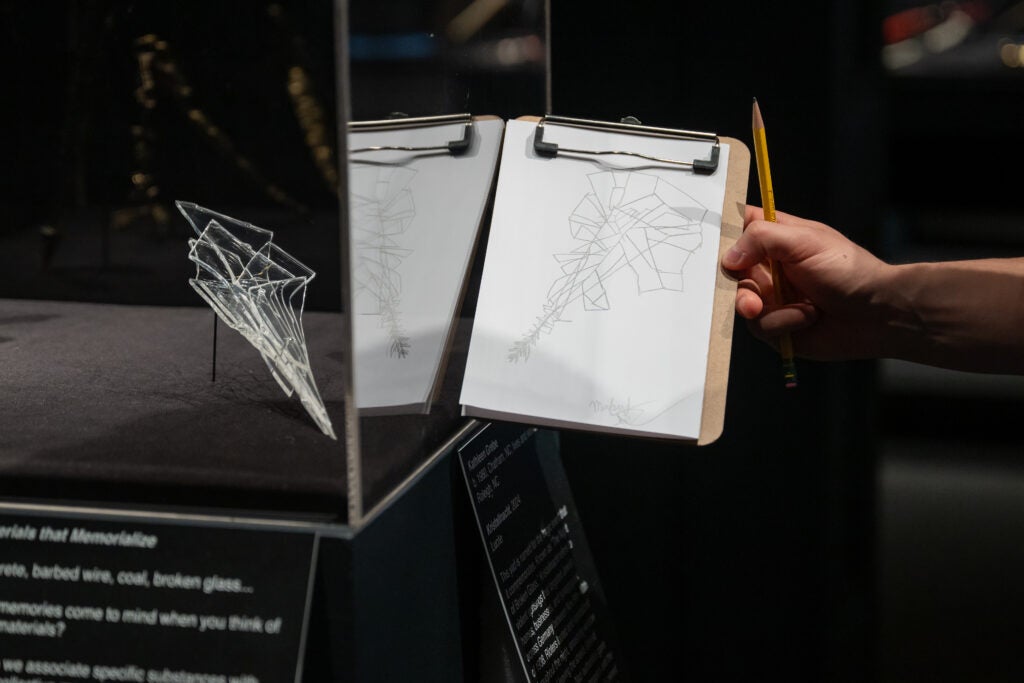

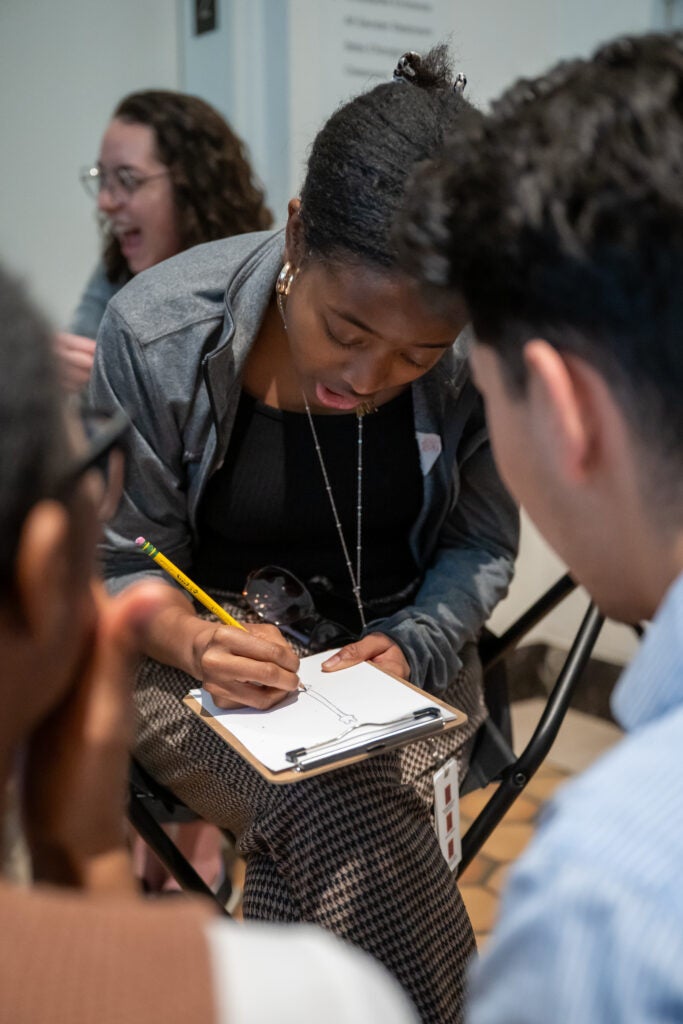

“It was a nice break to have dedicated time set aside to look at art, talk about it, and see how it connects to what I do on a day-to-day basis,” said first-year medical student Aryaman Singh. “I didn’t see how they were going to bring the two {art and clinical care} together. But we ended up doing a whole assignment on drawing and describing, and the parallels with clinical practice, like taking a patient history and presenting a case. It was poignant.”

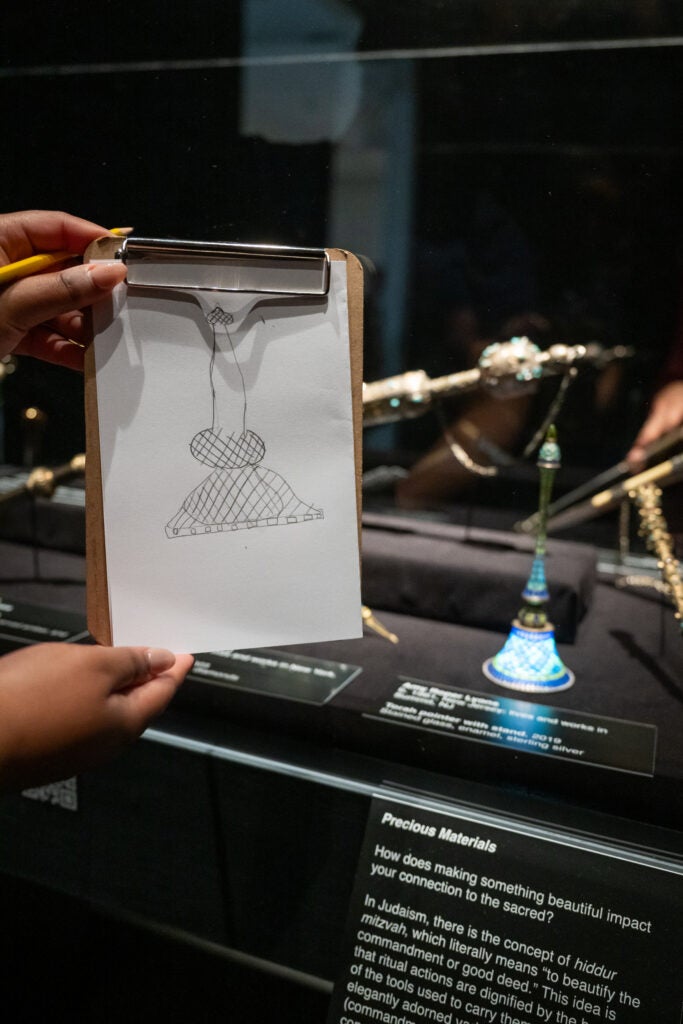

Students complete three exercises: collective visual inventory of representational art, using art history’s Visual Thinking Strategies; team drawing and describing, using three-dimensional objects; and word association, in response to abstract art. For each exercise, Clinician’s Eye uses museum artworks from whatever is on temporary or permanent display.

“Each exercise treats the work of art as a ‘third thing,’ to use educator Parker Palmer’s term. Focusing on this third thing, we approach at a slant a subject that might otherwise be too powerful, too painful, too personal to confront directly,” explained Professor Childress. “Art objects as third things can catalyze conversations about illness, social and healthcare injustices, loss and grief, and where in a broken world do we find inspiration and joy.”

Integrating Arts and Humanities into Medical School Curricula

The Association of American Medical Colleges’ (AAMC) 2020 report, The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education, urges medical schools to integrate arts and humanities into their required curricula. According to the AAMC, art-based learning contributes significantly to preparing compassionate, reflective, and resilient physicians, sustaining their well-being, and staving off burnout. At UVA, for a dozen years, and counting, Clinician’s Eye has been working to do just that.

While originally created for medical students, Clinician’s Eye is available to—and increasingly used by—residency programs and clinical departments, to exercise the same set of healthcare professionals’ core skills. An adaptation is being planned for biomedical scientists: Investigator’s Eye. Workshops can be scheduled with the museum, usually at the interested unit’s convenience.

Photos by Cece Rooney.