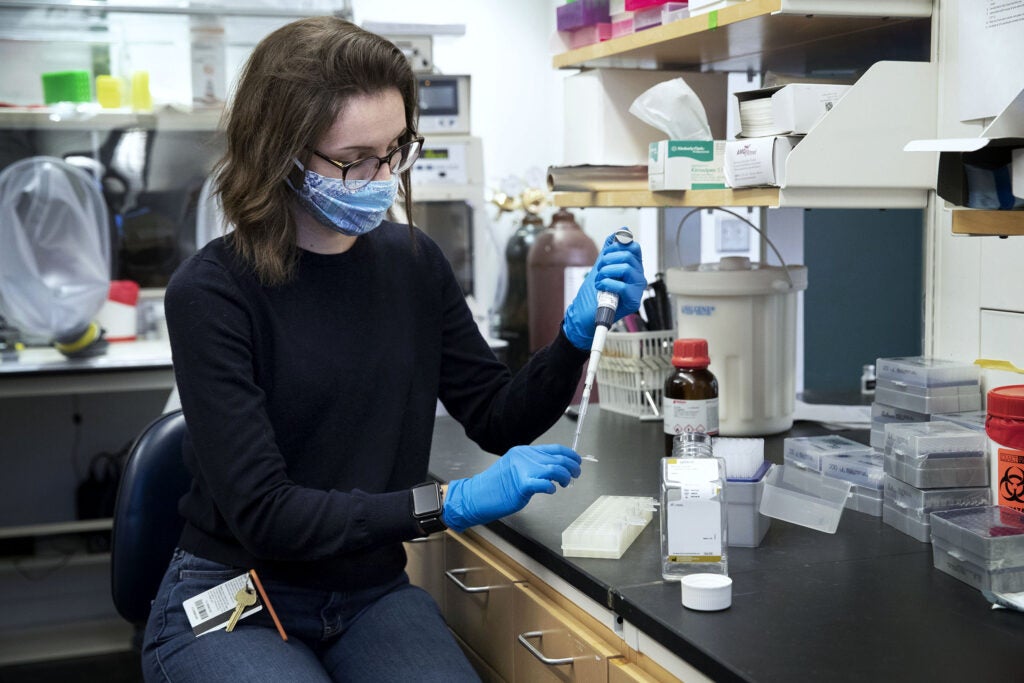

Allie Donlan is in the fourth year of her Ph.D. program at UVA, studying biomedical sciences. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Even as the coronavirus pandemic began to grip the world in late February and early March, University of Virginia Ph.D. student Allie Donlan did not necessarily picture herself working on treatments for the strange new virus.

Donlan, a senior graduate student researcher in Dr. William Petri’s lab, was generally focused on the immune response to Clostridium difficile, or C. difficile, infection, and specifically focused on IL-13, a cytokine, or small protein, secreted by the immune system that was proving particularly helpful in fighting C. diff.

But Petri – a chaired professor of infectious diseases and international health at UVA and vice chair for research in the Department of Medicine – was curious if the immune response to the novel coronavirus could be manipulated to protect from COVID-19, as he and Donlan had observed with C. difficile. With the support of the Department of Pathology, Petri and Donlan began analyzing the immune response to the new coronavirus in samples from the first COVID-19 patients at UVA.

To Donlan’s surprise, they found the same cytokine that she had spent years studying: IL-13.

Donlan learns more every day about how our immune system responds to COVID-19 and how immunotherapies might help patients. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

“It was fortuitous that the cytokine that came out of patient plasma was the exact cytokine that I study in C. diff,” she said. “We were switching from studying a bacteria in the gut to a virus in the lung, but we didn’t have to learn a whole new set of information.”

Six months later, Donlan, along with Petri, research professors Mayuresh Abhyankar and Barb Mann and researcher Mary Young, has learned that high levels of IL-13 are associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes, including an allergic immune response, called a Type 2 immune response.

Donlan is now working on possible immunotherapies that could manipulate IL-13 and other Type 2 cytokines to block the production of IL-13, and, she hopes, prevent that deadly immune response. The interventions have been successful in mice, suggesting that they have promise for humans as well.

Petri, Abhynakar and others are also working on vaccine possibilities, and particularly on ways to ensure that a COVID-19 vaccine promotes long-lasting immunity.

The whole experience, Donlan said, has been challenging, gratifying and educational – something she has been building toward ever since she read “Hot Zone,” by Richard Preston, in high school, a nonfiction thriller that traces an Ebola outbreak.

“I was so fascinated by this virus that I decided I wanted to work in virology,” Donlan recalled. “I studied virology at Florida State and then when I came to UVA, I got involved in bacteriology, a tangent from my original focuses on viruses. The pandemic, in a way, has brought me back to that original focus.”

Donlan chose UVA because she liked the community – the camaraderie that she saw among students and researchers, and the wider appeal of the University and the Charlottesville area. Petri, for one, is very glad she did; he called Donlan one of the best graduate students he has ever worked with.

“That is not hyperbole, and I have worked with some spectacular graduate students,” Petri said.

For her part, Donlan has come to appreciate camaraderie and collaboration among colleagues even more during the pandemic, as many labs have shifted from their usual work to focus on COVID-19.

“We primarily focus on enteric infections, so lung infections have been pretty new to us [in Petri’s lab],” she said. “We have been collaborating a lot with people we have never worked with before, who have knowledge and resources that are challenging us in new ways.

“It’s been a challenge, certainly, but ultimately a very rewarding and interesting experience.”

MEDIA CONTACT

Caroline Newman

Associate Editor

Office of University Communications

cfn8m@virginia.edu | (434) 924-6856

Filed Under: Clinical, Featured, Media Highlights, Research