November 30, 2023 by Kim Kelley-Wagner kak2cj@uvahealth.org

What a Couple of Fellows Can Do

When Doctor Brian Wispelwey arrived at the University of Virginia as a fellow in 1986, he had probably seen and treated more cases of HIV than most of his mentors. Wispelwey saw his first cases of HIV while a fourth-year medical student in 1981 while helping run a clinic as Chief Resident in Boston. At the time, common thought was that AIDS mainly appeared in large city populations, but the medical community would discover that to be a misnomer.

According to the World Health Organization, those infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has reached more than 80 million people, and about 40 million have died from acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), the most advanced state of the disease, since the start of the pandemic (World Health Organization, HIV and AIDS, Key Facts, 2023)

According to the World Health Organization, those infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has reached more than 80 million people, and about 40 million have died from acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), the most advanced state of the disease, since the start of the pandemic (World Health Organization, HIV and AIDS, Key Facts, 2023)

In the United States, AIDS became the leading cause of death for all Americans ages 25-44 years old in 1994. By 1997, AIDS-related deaths declined by 47 percent, nearly half, due to the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy. (CDC Weekly, Mortality Attributable to HIV Infection Among Persons Aged 25-44 Years — United States, 1994, 1996/PubMed, U.S. AIDS death rate decreases by nearly half, 1999)

As Chief Resident at Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital, Dr. Wispelwey became involved with enrolling patients in the first AZT trials; AZT (zidovudine) would change everything. After completing residency, Wispelwey narrowed his choices between Massachusetts General and UVA in deciding where to do his Infectious Diseases fellowship. With all things being equal, you can thank Charlottesville’s more reasonable cost of living for our gain.

Brian Wispelwey was number one in his medical school class; he could have chosen any field or specialty he liked. But it was the fact that everyone else was running away from HIV/AIDS that held an attraction, “I thought, maybe this is where I am supposed to be; I can make a difference.” Dr. Wispelwey chuckled when he recalled conversations with colleagues in other specialties who have been baffled by the choice of concentrating his efforts on treating patients with HIV. “They clearly don’t get it,” he smiled.

With his residency clinic knowledge, he and another fellow with HIV experience created a clinic within UVA to bring patients to one central location for all their treatment needs. After his fellowship, Wispelwey was offered a faculty position and has continued running the Clinic.

Initially, the only available funding was from the state, and the Clinic’s staff was minimal. In 1990, Congress passed the Ryan White Care Act, and grant funding became available. These funds included provisions for early intervention, such as HIV testing and counseling, which was an essential step in preventing and helping to stop the progression of the disease. It also provided prenatal and maternal care for HIV-affected mothers and children born with the infection.

About the time the Ryan White Act was working its way through Congress, Dr. Greg Townsend was finishing his fellowship at UVA. Though he found HIV and AIDS a fascinating disease to study, he had not planned on becoming a doctor working strictly with HIV patients. “Everybody died,” he recalled. Emotionally, it could be a complex space to occupy as a physician.

However, Dr. Townsend surprised himself one day when asked what he planned on doing with his future after fellowship. “I heard myself saying, ‘I want to work with HIV patients.’ and thought, wait, did I just say that? Can that be right? But I realized that with the development of the new drugs and treatments, people were living well, living longer and healthier lives.”

He went on to explain his life’s ambition. “I wanted to be a primary care doctor; I wanted to be Marcus Welby! A kindly doctor who cared for everyone cradle to grave; everybody loved me,” he laughed. “That was my idea of a physician; you took care of everybody.” Townsend has outstretched his arms on his desk, bringing them together as if embracing someone or gathering in his ‘everybody.’

He continued, “So what has happened with HIV is that I have fulfilled my dream of being Marcus Welby. I have patients in my Clinic that I have been seeing for thirty years. And it’s wonderful! It’s such a gratifying experience.”

By the mid-90s, the new drugs and combined therapies were so successful that incredible health and life expectancy improvements changed within a year. In 1995, the University of Virginia’s HIV clinic took in 160 new HIV/AIDS patients, 130 of whom died. The following year, 1996, the Clinic admitted 170 new patients with only a death rate of two—an incredible medical triumph.

Nobody is dying of HIV right now; patients live with it. Babies are no longer automatically born with the infection if their mothers are HIV-positive as long as she is taking the appropriate medications. It has been decades since a child was born HIV-positive at UVA. So, a shift in care has both improved and evolved.

Excellence Amplified

Everlyne Sawyer enters a room like a forward force. Her enthusiasm fills the space the moment she steps into it. Everlyne has a firm handshake and a quick smile that reaches her eyes. She is a person who is both earnest and laughs easily, someone you immediately want as a friend. Ms. Sawyer has been the Ryan White Center’s Program Manager for the past four years; she knows every employee, every patient, and all the stats. It quickly becomes evident that her compassion in that knowledge drives her enthusiasm. She pointed to success after success. Introduced every person working at the Clinic with pride and praise for their daily accomplishments.

Everlyne Sawyer enters a room like a forward force. Her enthusiasm fills the space the moment she steps into it. Everlyne has a firm handshake and a quick smile that reaches her eyes. She is a person who is both earnest and laughs easily, someone you immediately want as a friend. Ms. Sawyer has been the Ryan White Center’s Program Manager for the past four years; she knows every employee, every patient, and all the stats. It quickly becomes evident that her compassion in that knowledge drives her enthusiasm. She pointed to success after success. Introduced every person working at the Clinic with pride and praise for their daily accomplishments.

The University’s Ryan White Center is indeed worthy of praise, as evidenced by its many accolades. It is recognized as among the top five Ryan White clinics by the Human Resources Services Administration (HRSA). It’s named Excellence of Comprehensive Clinical Care nationally and Excellence in Patient Quality Improvement. Additionally, its Quality Improvement Plan in 2022 is statewide renowned, and they were featured at the VDH Statewide Quality Summit in 2022. The Center is a source of clinical innovation for other disease management clinics at the University. It is an outstanding platform for education and research at UVA and the community. Its HIV patient viral suppression is at 91.50%, which is above Virginia state and national goals. But most importantly, it serves a majority-minority, socio-economically disadvantaged population with many barriers to life-saving medical care, ending the HIV epidemic.

The Clinic currently has 974 patients, not all from the immediate Charlottesville area. Some come from distant parts of Virginia, some even from other states. One of the many reasons the Ryan White grant is essential is that it helps with transportation, and many would not be able to get medical care without it. When visualizing medical treatment, some might only consider medications and a doctor’s attention. But when the creators of the Ryan White Act wrote it, they wanted to be sure each patient’s needs were being met beyond the basics of medical intervention. After all, if a person is homeless or hasn’t eaten, making sure they take daily medication may not be a priority.

The program’s official name is the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency Act, which became federal law in 1990. It not only provides for HIV medical care but also psychiatric and psychological mental health treatment, OBGYN care, anal PAP and anoscopy (HRA) services, nutrition and substance abuse counseling, and patient support groups. It helps pay for on-site pharmacy services, HIV/AIDS resources, and linkages for an inmate program (CHARLI) for currently and formerly incarcerated individuals, as well as medical and non-medical case managers and community health workers. The Clinic is comprehensive; all services are available in one place, so the patient only needs to visit one location, and providers come to them as necessary.

The program’s official name is the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency Act, which became federal law in 1990. It not only provides for HIV medical care but also psychiatric and psychological mental health treatment, OBGYN care, anal PAP and anoscopy (HRA) services, nutrition and substance abuse counseling, and patient support groups. It helps pay for on-site pharmacy services, HIV/AIDS resources, and linkages for an inmate program (CHARLI) for currently and formerly incarcerated individuals, as well as medical and non-medical case managers and community health workers. The Clinic is comprehensive; all services are available in one place, so the patient only needs to visit one location, and providers come to them as necessary.

Dr. Greg Townsend explained, “We’re here to make sure our patients get the best care they possibly can in a way that causes them the least problem and effort on their part. Most of our patients have a lot of other things going on. They don’t need to worry about whether they will be able to make it to multiple doctor’s offices or afford medications. So it is vitally important for us to make sure – to the extent that it is possible – that we take care of our patients medically, and they don’t have to worry about their care.”

As impressive and essential as these statistics and functions are, its people are the biggest reason for the achievements of the University of Virginia’s Ryan White Center. Everlyne Sawyer wants to be sure that all staff at the Center, no matter their role, understand that each patient may be struggling with many more challenges beyond just their health condition. She said, “We have to meet them where they are, no matter what. That is why we are so successful – everyone here understands that.”

Everlyne continued, “Another reason for the Clinic’s success is how everyone works as a team. For instance, the entire team gets an email if a patient comes in and their viral load isn’t what it should be. The goal is to quickly get the patient back on track, and a plan for that will be in place within two days. Without the grant, we couldn’t take that all-hands-on-deck approach and do what we do now. If we haven’t seen or heard from a patient in a while, we don’t assume everything is going well; we make contact to be sure.”

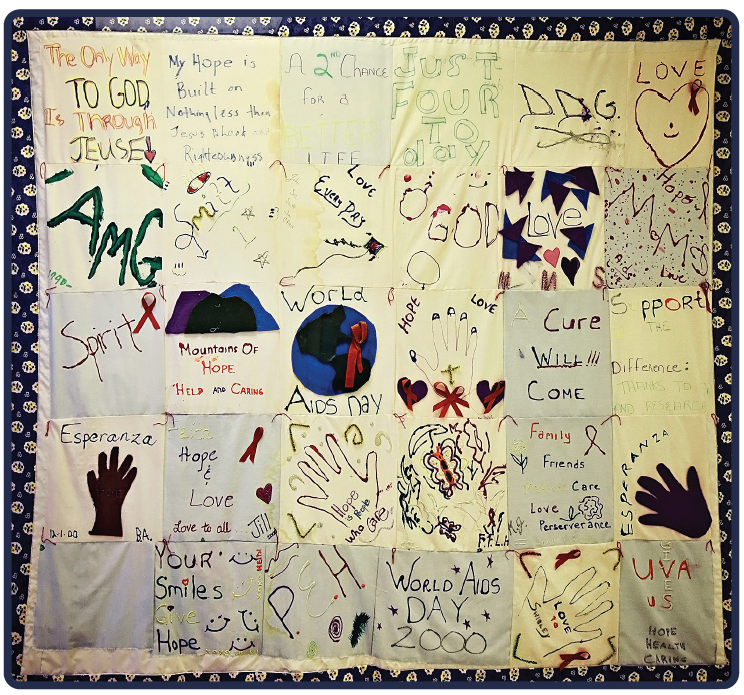

The result of this kind of caring, besides the impressive medical results, is people who mean something to each other beyond a clinical setting. On the walls hang framed quilts and art pieces made by patients. They bring baked goods and make small handmade gifts. Incredible care has been shown to patients; in turn, like friends, they reciprocate in ways they can.

Everlyne says that working at the Ryan White Center has put into perspective the disparities that continue to exist in our communities, not only in attaining medical care but in assuring basic human needs such as food, housing, and companionship. Sadly, a stigma remains for many around those with HIV, and there are still ample numbers of the misinformed. For some who have HIV infection, those who treat them medically may be one of the few social connections they have. “It grounds you,” [knowing this] says Everlyne. “This clinic model is not that expensive to emulate. Doing great work and patient care doesn’t require a lot of money and degrees; it just takes good medicine and good people.”

It Takes a Special Kind of Person

Operating the Clinic and retaining staff hasn’t always been easy, not only from a financial perspective, having to fund operations primarily from grants, but also from an emotional one. Brian Wispelway reflected, “We all enter into medicine to save lives, and we would often lose a lot of staff not because they weren’t passionate about the work, but because they couldn’t stand the loss of so many, mostly young people. Death is a reality; it’s going to happen. Our goal in medicine is always supposed to be prolonging quantity certainly, but also quality of life. Unfortunately, we often get too much into quantity and not enough into quality.”

Operating the Clinic and retaining staff hasn’t always been easy, not only from a financial perspective, having to fund operations primarily from grants, but also from an emotional one. Brian Wispelway reflected, “We all enter into medicine to save lives, and we would often lose a lot of staff not because they weren’t passionate about the work, but because they couldn’t stand the loss of so many, mostly young people. Death is a reality; it’s going to happen. Our goal in medicine is always supposed to be prolonging quantity certainly, but also quality of life. Unfortunately, we often get too much into quantity and not enough into quality.”

The phrase, ‘It takes a special kind of person,’ was voiced multiple times while speaking with those at the Center. Each was talking about their colleagues, not only their compassion for patients, but how often they ‘go the extra mile’ to ensure a patient gets their medication, has transportation, food, or just someone to let them know they’re cared about. All those who work at the Ryan White Center do so because they want to work at the Ryan White Center. It changes a person.

Dr. Wispelwey continued speaking about early years at the Clinic, “Here [treating HIV/AIDS patients], I realized fairly quickly that you developed relationships with people, and they were so thankful for their care. They were going to die, but we had helped them deal with that and helped get them further along than they probably would have. They still died and died fairly young, but it switched my paradigm of thinking from, ‘don’t just stand there, do something,’ to sometimes it’s ‘don’t just do something — but stand there.’” After a pause, he went on, “Often doctors have been criticized, and rightfully so, that when patients are at the point of dying, we let nurses and palliative care take over, and we’re gone. No! That’s when they need us the most. We’ve been involved with them this far; don’t just walk away.”

Despite the loss and death rate in the initial days of HIV/AIDS, by fighting for his patients who found it so difficult to get services and support, Dr. Wispelway realized that he was making a difference; he came to understand that “survival wasn’t always the only measure of success.”

“When I began to think more on these things, I found that the term ‘physician’ means ‘to care’; it doesn’t mean ‘to cure.’”

Wispelwey’s philosophical way of thinking isn’t an accident; the tradition in which he grew up instilled a belief that “it’s not all about you; you’re here to make a difference.” His parents implanted a sense of community responsibility; his father, in particular, was dedicated to volunteer work despite his busy schedule. “Do what you can do. The bottom line is that you want to look back on your life and feel good about what you’ve done,” said Wispelwey.

Greg Townsend’s family also influenced his life’s trajectory, “My parents inculcated in me that my ‘job’ for the rest of my life was to make the world a better place. That’s what I get to do here every day. I get to make the world – a little bit of it – a better place. I get to help change the lives of people whose lives might otherwise not be as satisfying, healthy, or rewarding as they might be. I get to be a part of that process. And I get to do it daily with people who have the same mission that I do. It’s incredibly satisfying.”

Every person spoken with seemed to share this philosophy to make a difference, to make the space they occupy better than they found it. Each is unique, yet they share a common goal: the betterment of the lives of those who pass through the Center’s doors. And regardless of role, each plays their part with purpose. Sincerity may seem a small thing, but assuredly, it is not, especially to the vulnerable.

There remains no remedy for HIV infection; however, it no longer holds those affected by it in the blinding grip of despair that it did when it first rampaged in the early days of ‘the plague,’ Research continues on better therapies and possible cures, including here at the University of Virginia. Through the evolving stages of the disease and its treatment, dozens of care providers have assisted in many roles to make the worlds of those who come to UVA’s Ryan White Center a better place. Two doctors have been there from the beginning while still in their fellowships and remain four decades later: Brian Wispelwey and Greg Townsend. Undoubtedly, what they have achieved was well worth it, a thing done well and to be proud of. Anyone should be able to get that.

Equations

Most people might make happiness their life’s goal, but happiness cannot be realized without taking action to attain it. What makes each individual happy undoubtedly differs; however, happiness will not be achieved without purpose. If what one does is of value, if it is useful, that will produce happiness. Therefore, happiness is the byproduct of usefulness. Ralph Waldo Emerson expressed it perfectly: “The purpose of life is not to be happy. It is to be useful, to be honorable, to be compassionate, to have it make some difference that you have lived and lived well.” This quote by Emerson sums up the Ryan White Center and each person who now or ever has worked within its walls: people with an incredible commitment to a common purpose and the evidence of comfortable happiness. May we all be so lucky to have made some difference and lived so well.

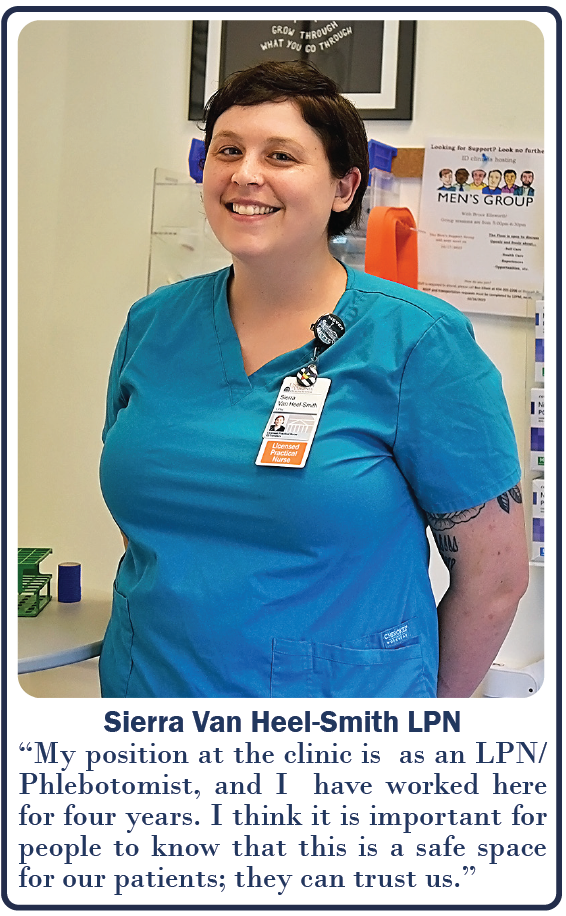

Author’s note: Many exceptional people work in the Ryan White Center; only a few have been highlighted here. Some of those pictured happened to be available to me on the day I visited, and they were kind enough to let me photograph them and answer my questions. There are dozens more that have not been mentioned by name, working with patients and behind the scenes. There is no one hero; there is an entire team of them. They’ve worked quietly for nearly forty years, tucked into a corner of the Infectious Disease Clinic. I realize that a few words in an article are not enough to express the positive impact this group of remarkable individuals has made in the lives of so many, but it has been my honor to have tried.

Author’s note: Many exceptional people work in the Ryan White Center; only a few have been highlighted here. Some of those pictured happened to be available to me on the day I visited, and they were kind enough to let me photograph them and answer my questions. There are dozens more that have not been mentioned by name, working with patients and behind the scenes. There is no one hero; there is an entire team of them. They’ve worked quietly for nearly forty years, tucked into a corner of the Infectious Disease Clinic. I realize that a few words in an article are not enough to express the positive impact this group of remarkable individuals has made in the lives of so many, but it has been my honor to have tried.

Read Full December 2023 Issue

Filed Under: Clinical Research, DOM in the News, Education, In the Know, News and Notes, Notable Achievements, Top News